Open Archways Catalog

-

How do you tie a mitpachat? by Hannah Finkelshteyn, Curator

Medium: Poetry, Photography and Music

Artist Statement:

"Love is often contrarian. Shaped by parental, cultural, and societal expectations, it is an abstract ideal — a yearning that rarely unfolds like the childlike dream. It's a journey of heart, mind, and sometimes, the forbidden.

When love flourishes, all preaching dissolves. Cultures and faith turn borderless as pathways to humanity emerge through the lens of "We are one." And if one is truly lucky, love's breath transforms the unattainable into a soulmate."

-

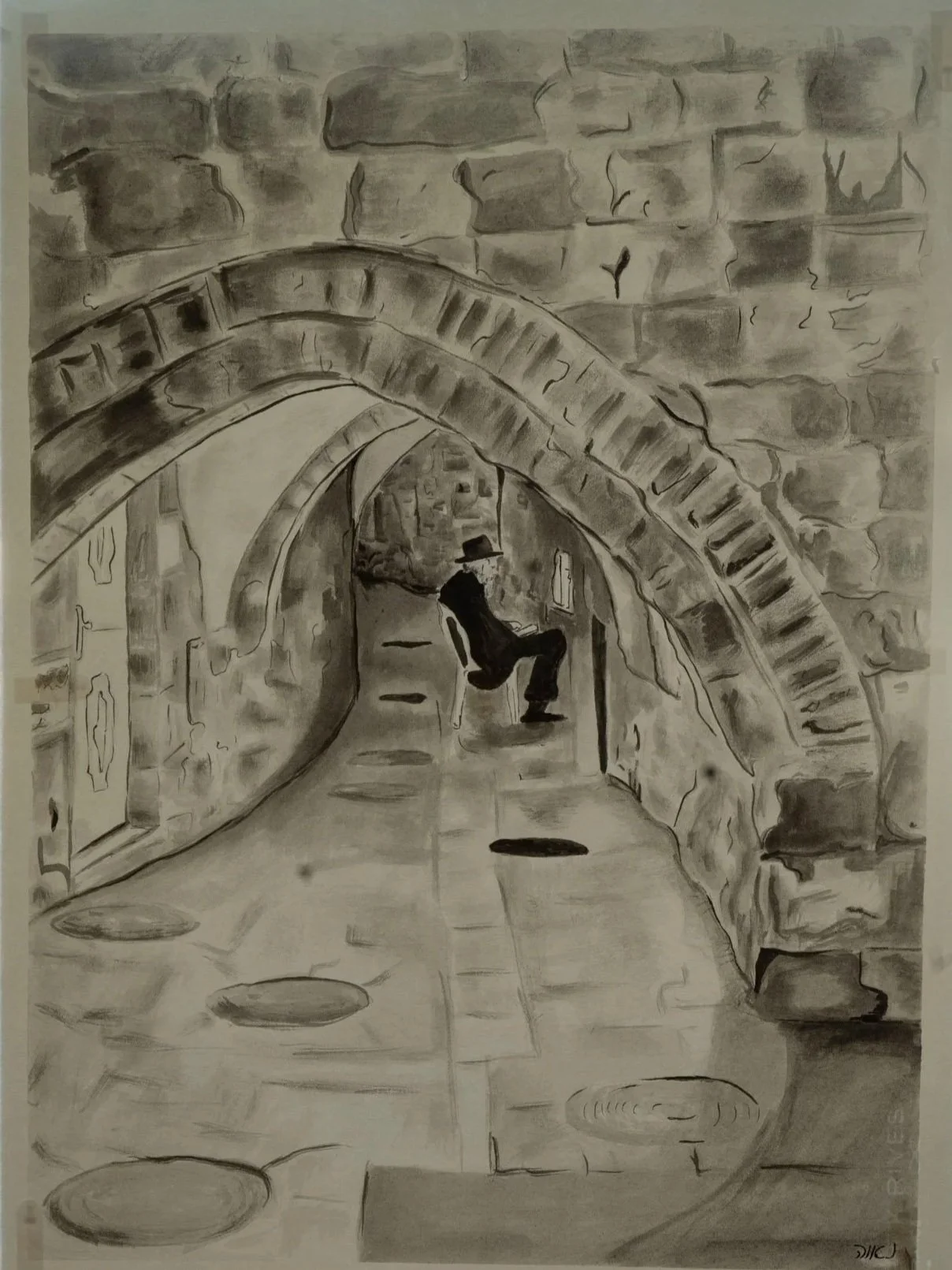

הנרות הללו אנו מדליקין על הניסים ועל הנפלאות, by Nava Gluck

הנרות הללו אנו מדליקין

על הניסים ועל הנפלאות

, or “These lights we light, because of the miracles and the wonders,” depicts a scene I witnessed during Chanukkah in the Old City of Jerusalem. An old man sat alone, lighting his candles and saying their blessings. A warmth emanated from the flame. The title derives from a song sung year after year, for thousands of years, as we lit the Chanukkah candles. I was reminded of this scene when talking in the meetup sessions, of the warmth of ritual and tradition, and the light that each of us can bring into the world.

-

33°30'42”N 36°18'29"E by Muna Al Fadl

Reconstructing the shared history of Muslims and Jews in the Old City of Damascus through Google Earth imaging of the Jewish Quarter was my original intention, but when searching for street view imaging I came to an unfortunate reality. There are none in the Jewish Quarter. On the Google Earth street view in Syria, there are no Google cars driving and documenting Damascus, it is all panoramic images uploaded by tour guides advertising their business or people documenting where they live. Since the Jewish Quarter has been mostly abandoned since 1992, there seems to be no one documenting it.

This piece is no longer a documentation of a shared history in Damascus, humanity’s oldest city. Now it pulls from a different conversation shared between the artists over coffee. While debating our relationships with our own religions the topic of gender expectation emerged. In my upbringing, gender or sex expectations never had a role in my life or religion. There were small things here and there, but being Muslim and a girl never interfered with each other. However, as a child, at my aunt’s house in Sharjah, I began to observe sex segregation. Sitting at family gatherings, I, of course, sat with women. As a young girl I was loud with a curious interest in politics. The circle of men next to us would speak about corruption and war-criminals, peaking my interest. As I chirped into their conversation, I would get reprimanded and told to leave the men alone. Over time I realized the amount of drifting ears from the two circles at family gatherings, but no drifting voices. One evening in my aunt’s house, I burst into uncontrollable laughter at this observation. Men listening to women, women listening to men, but all criticizing the same corrupt politician. My father asked me why I was laughing so much. How stupid to have the same conversation but not together? Now, we all sit together.

As I heard the experiences of Jewish artists with gender expectations in their communities, I couldn’t help but observe my own.

When searching on Google Earth, I found a panorama a few blocks from the Jewish Quarter next to the Umayyad Mosque, and immediately it brought me back to both conversations, one as a child in my aunt’s apartment in Sharjah and one in a coffee shop in the East Village. Men and women sitting separately, not interacting with each other. And the strangers who shared their intimate relationship with religion.

-

The Night Of Two Moons by Gal Cohen

This mixed-media installation brings together works from several of my ongoing series—Home Sick Home, Ghost Print / Haunted House, and others—that explore the layered experience of the self and the fragmented identities that compose it. Through painting, drawing, and printmaking, I investigate how personal, political, and ancestral narratives intersect within the Body and the Home.

As a Jewish queer mother and a peace activist from Israel, currently living in New York for the past decade, I often find myself suspended between definitions—belonging and alienation, homeland and exile, self and other. In the current moment of political upheaval and war between Israel and Palestine, these tensions feel especially charged.

When I search for grounding, I return to the notion of ancestral motherhood—a force that is both ancient and immediate. Motherhood, in its universality, transcends borders, ideologies, and belief systems. It is a shared human experience that connects us across conflict, culture, race, and faith. Their grief, tenderness, and resilience mirror one another. To mother is to create, to sustain life against all odds—and that, to me, stands as the radical opposite of war.

This installation presents the self through various symbolic and expressive forms—fragmented figures, architectural motifs, and hybrid bodies merging the home and the human. These images act as metaphors for both protection and vulnerability, for the collective and the intimate. Together, they form a visual meditation on belonging, loss, and the quiet, enduring strength of those who nurture life amid destruction.

-

Window Shopping at Moonrise, by Eaint Maung

Window Shopping is an ode to when I was 14 and in the process of looking into other religions as well as re-examining the one that I was born into. I had had enough with Saturday School and how my religion was being taught to me, so during the next year, I looked into other religions. I went to their places of worship, and I spent my weekends in churches, synagogues, and even looked back into Buddhism (as I was surrounded by it growing up in Burma). In each of the spaces, I felt a sense of safety and community. Despite the differences from my own religion, I noticed a lot of overlap. I think looking into other religions made me want to learn more about my own. I’ve always said that reverts and converts have better appreciation of the religion they chose because they didn’t have the opportunity to take it for granted.

-

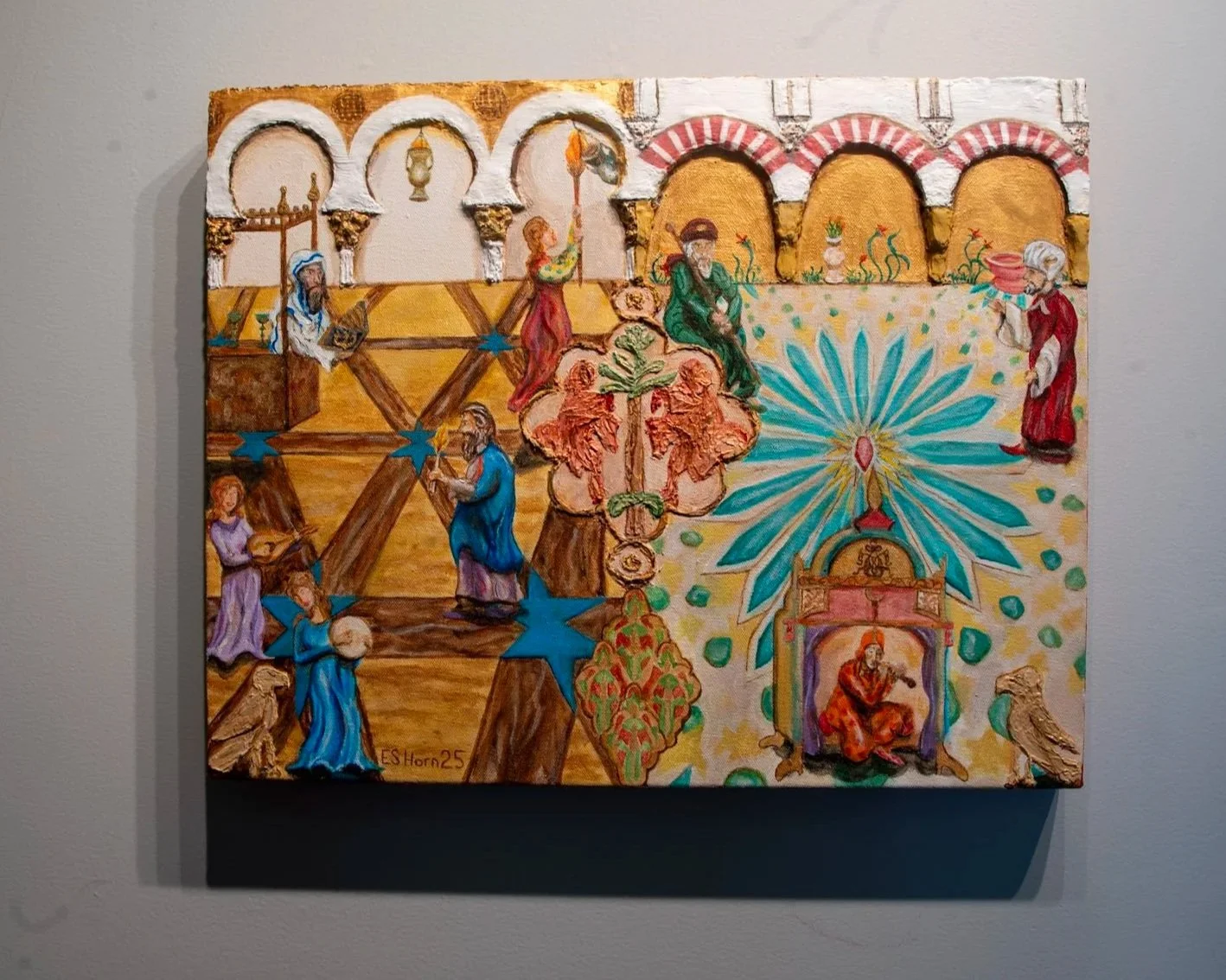

la Felicidad de al-Andalus by Eric Scott Horn

The last two months were an intense learning process. It started with the Open Archways group discussions and continued through a several-day crash course in Medieval Spanish Art History. Then it evolved through a radically different use of artistic materials and styles than I had previously experienced.

When I started the painting, I was only certain that I wanted to place the arches from the Ibn Shoshan Synagogue and Great Mosque at the top. I also had a vague notion that I wanted to use a set of figures from the woodworking panel or the Pyxis facing each other in the center. However, I was not sure which ones would be the best centerpiece or what style I would use. I only decided a few moments before I started making the horsemen.

I have used stucco for accents in a couple of paintings, primarily for raised sections or texturing. This was the first time I used it on a long continuous section of architecture. The arches turned out to be far more difficult than I expected. The stucco was too rough and clumpy, and the joint compound was too fluid. So, it took a lot of work and re-work to get the shapes right. When I used stucco for the center piece and birds, I felt that it would be more interesting if it appeared as hammered metal features than smoothed out shapes to resemble wood or ivory structures. I also felt metal images presented a better overall composition due to the metal adornments of the synagogue and the golden backgrounds of the Islamic paintings.

As difficult as the arches were to construct, the floors presented the greatest challenge. It was difficult to perceive how to properly arrange any kind of perspective, particularly since I made Escher like effects with the top two Jewish figures. But after some difficult hours, I was able to capture the effect I wanted. In the end, I am very pleased and proud of the painting.

-

Turk-uoise, Battal, by Ali and Ipek Saracoglu

Turk-uoise explores the meeting point between blue and green, two colors that shaped my earliest sense of the world. Although green has always been my personal favorite, this project pushed me to work within a blue-centered palette. Turk-uoise became the bridge, drawing from the turquoise spectrum that naturally blends both. The palette also connects to childhood summers on the Aegean coast near Kuşadası, where seaweed floated through water that was never purely blue or green, but always something in between. That mixture has stayed with me.

This piece moves away from classical Ebru forms. Instead of the symmetry traditionally associated with the art, Turk-uoise uses a wave technique developed by my father and his master, an innovation within our family’s practice. My sister and I have continued shaping this contemporary style and sharing it more widely. Creating these waves feels like working with the rhythm of the ocean: layered, shifting, and quietly dynamic.

The Open Archways cohort also influenced this work. Conversations around color, process, and emotional tone encouraged me to refine the palette and trust that this hybrid turquoise could hold both memory and meaning within the broader series we are presenting. Watching others work fostered a sense of shared exploration that pushed me further into fluidity and motion.

Turk-uoise is one of several pieces my sister and I created for this exhibition, all connected through color relationships and variations in pattern. While Ebru carries deep spiritual roots, particularly within Sufi traditions, I always prefer to let those meanings remain in the practice itself. My hope is that the movement in the piece invites viewers into their own contemplative space, much like watching the sea shift under changing light.

Battal is the earliest and most essential form of Ebru—simple droplets of color on water that become the foundation for every other pattern. Though often seen as basic, it is one of the most challenging to make because nothing can be hidden. Every movement, every decision, sits fully exposed. That purity is what drew me to let Battal stand on its own for this piece.

While working with the Open Archways cohort, we often talked about tradition and modernity, how they coexist, how they shape each other. I originally planned to create a sheet that blended both: half Battal, half a more contemporary, wave-like pattern. But during the process, one pure Battal emerged with such clarity that it felt complete without the modern half. It reminded me that tradition doesn’t need to be reinvented to belong today, sometimes its strength is precisely in its original form.

The choice of blue carries both emotional and cultural significance. On a personal level, it reflects the calm and introspective mood I brought into the work. It’s also the color of my hometown Izmir and the Aegean Sea, and a meaningful color in both Judaism and Islam. Through these layers, blue becomes a connector between different geographies, memories, and faith traditions across the Mediterranean.

Creating Battal is how every Ebru session begins, testing the water, the paints, the interaction of pigments as they expand and settle. Because of that, the piece captures a moment of balance between intention and the natural movement of materials. Ebru is an abstract form, so I don’t want to guide anyone toward a specific interpretation. My hope is simply that viewers let the shifting blues take them wherever their own emotions lead.

Being part of this cohort encouraged me to trust this simplicity and commit to a piece rooted deeply in tradition.

-

L'Chayim (To Life), by Amee J. Pollack

Earthenware plate and book, acrylic

An appreciation of family, tradition, and ritual lies at the heart of Jewish life, and among the holiest of holidays is Passover, which commemorates the Jewish exodus from Egypt. Central to this observance is the Seder—literally meaning “order”—a ritual meal rich with structure, symbolism, and storytelling. Each symbolic food placed on the Seder plate abounds in meaning and allusion, allowing us to quite literally taste the story of liberation.

I modeled a Seder plate in clay, incorporating imagery of a rooted tree and a Haggadah (the Passover book) to honor the holiday’s enduring significance. The six mini-bowls on my Seder plate represent the traditional ritual foods:

1. The shankbone, symbolizing the lamb that was sacrificed on the eve of the Exodus.

2. A hard-boiled egg, representing both the festival offering and the renewal of spring.

3. Maror, or bitter herbs (grated horseradish), reminding us of the bitterness of slavery.

4. Charoset, a mixture of apples, walnuts, and wine, resembling the mortar and bricks made by the Jews while toiling for Pharaoh.

5. Parsley, symbolizing the backbreaking labor endured by the Jewish slaves.

6. Chazeret (romaine lettuce), a second bitter herb, which is combined with charoset in a matzah sandwich to represent the coexistence of bitterness and sweetness.

In my family, the experience of having my Uncle Jacob lead our Seders remains an indelible and cherished memory. It was during these gatherings that I first began to understand the power of symbolism—a revelation that would later fuel my artistic sensibility and creative path.

-

3 Phases of a Daughter, by Tori Serazi

We are daughters to our family and our religions. We grow up being taught by religion the same way we are taught by our families. Family, religion, and culture are ingrained into our bodies as muscle memory.

3 Phases of Daughter depicts three phases of a woman's faith and life.

The first phase of life is for learning, being curious, and being dedicated to everything we are taught with unnerving commitment. It's a phase that feels as if it has been climbed over quickly, but it is the foundation of our belief system.

The second phase is for chaos, self-doubt, confusion, and questioning of all things. A phase full of some of the worst of emotions, and some of the best. We sit on it with hope and use it as a cushion of memories. We pull from this phase of experiences to re-establish our morals and faith into the next phase.

The third phase is about development, growth, and finally—self assurance. Often in a woman's life, the beginning of the third phase means she is transitioning to an understanding of herself, her place in life, her family, her friends, her religion, and her place as a daughter. The third moon is embraced and loved when self-love is achieved. This piece was inspired by a recent meetup with artists at Open Archways Seeing women and men of different ages come together to talk about their connection to art and religion made me think about how I would express my emotions into my art.

My art often explores the struggles and experiences unique to women, and our conversations reaffirmed my desire to focus on this theme once more. As a Muslim woman, listening to the stories shared by other Jewish and Muslim women revealed a similarity: we are all navigating different phases of our journey as daughters to our respective faiths and lives.

The collective discussion felt like an intergenerational dialogue—as if I were both an older self answering a younger self's questions about my experiences, and simultaneously a younger self posing questions to those who have walked this path before me.

-

Hineini, by Miki Belenkov

In creating Hineini, I tried to build off of the group’s conversations around our individual navigations of age-old traditions and the identity-related narratives of our elders with our contemporary surroundings, priorities, and lifestyles. I wanted to explore the negotiations of what we agree to hold, what we choose to sacrifice, and the ever-changing shapes our identities take while maintaining their essences.

I was especially drawn to how these renegotiations seemed to manifest around the family table in both communities, which inspired me to repurpose a tablecloth as the containing surface for this reflection. I hoped to imbue the piece with a familiarity through the use of a domestic textile, something that is both so ubiquitous and so inherently intimate and personal. The domestic textile felt even more pertinent as a loving “battleground” to reflect on inherited experiences of exile and diaspora, which emerged in discussion between both communities as well. I saw the tablecloth as a space to look at what it means to connect to home when you’ve been displaced from it. Does the tablecloth join the family as a relic of homes long since lost, or is it a newly acquired echo of the fabrics that had once bore witness to our daily lives that were left behind? Maybe it’s a revival of what the table meant for those before us.

The Chinese food on our table was included to embody the mixed cultural nature of Diasporic identities and the multitude of ways cultural negotiations arise between all kinds of migrant communities, as well as a nod to the specific historical ties of New York City’s Chinese and Jewish communities. Being a New York Jew, there was something poignant about how a family meal of Chinese takeout felt so authentically Jewish to me, despite the fact that it’s laden with traif (unkosher foods). It’s this sharing of cultures and interweaving of histories that felt like a fitting metaphor for what Open Archways set out to highlight about what’s shared between Jewish and Muslim communities.

In trying to develop Hineini, I struggled with how to present my Jewishness authentically while maintaining palatability to a wider audience. So much of my family history, as well as the past few years, have given me and my community an abundance to grieve over while simultaneously requiring that we defend our right to grieve. Somewhere in the endless cycle of grief and defense, I found myself expending more mental energy trying to prove to people what I’m not, rather than understanding and unapologetically embracing who I am. Not only did I assume no one wanted to see an artwork made in defense, I also didn’t really want to dedicate more energy to creating it. The realization that I was letting those who hate me define me led my pendulum to swing in the direction of centering radical Jewish joy. However, when I tried approaching the piece through that lens without acknowledging the context of the pain we’ve endured, it started to feel empty and dishonest. There were no roots to this joy.

It was only after bickering with my parents, storming off angrily, and eventually allowing their words to mingle with my own internal monologue, that I realized the core of Jewish joy is that we create opportunity for it even when there’s so much sadness to be felt. From there, the process took on a life of its own, and while I’m still unsure I resolved the question of the piece’s palatability, I feel like I managed to resolve the issue of authenticity. I found myself collaging together images from family meals, intermingling images of their immigration via Israel with those of our forebearers crossing the desert after being forced from their lands; setting them against a background of accounts of friends who blocked me without warning, shop doorframes holding reminders of the amulets that once graced them before being stolen by hateful passerbies, and a reference to the glass of temples destroyed thousands of years ago and now. I chose to integrate the symbol of the menorah to reference our collective resilience, the light we carry as a tribe and the choice to center light and life over the grief that we hold, while still illuminating and honoring its presence.

-

Defying the Unattainable, by Nadira Husain

Medium: Poetry, Photography and Music

Artist Statement:

"Love is often contrarian. Shaped by parental, cultural, and societal expectations, it is an abstract ideal — a yearning that rarely unfolds like the childlike dream. It's a journey of heart, mind, and sometimes, the forbidden.

When love flourishes, all preaching dissolves. Cultures and faith turn borderless as pathways to humanity emerge through the lens of "We are one." And if one is truly lucky, love's breath transforms the unattainable into a soulmate."

-

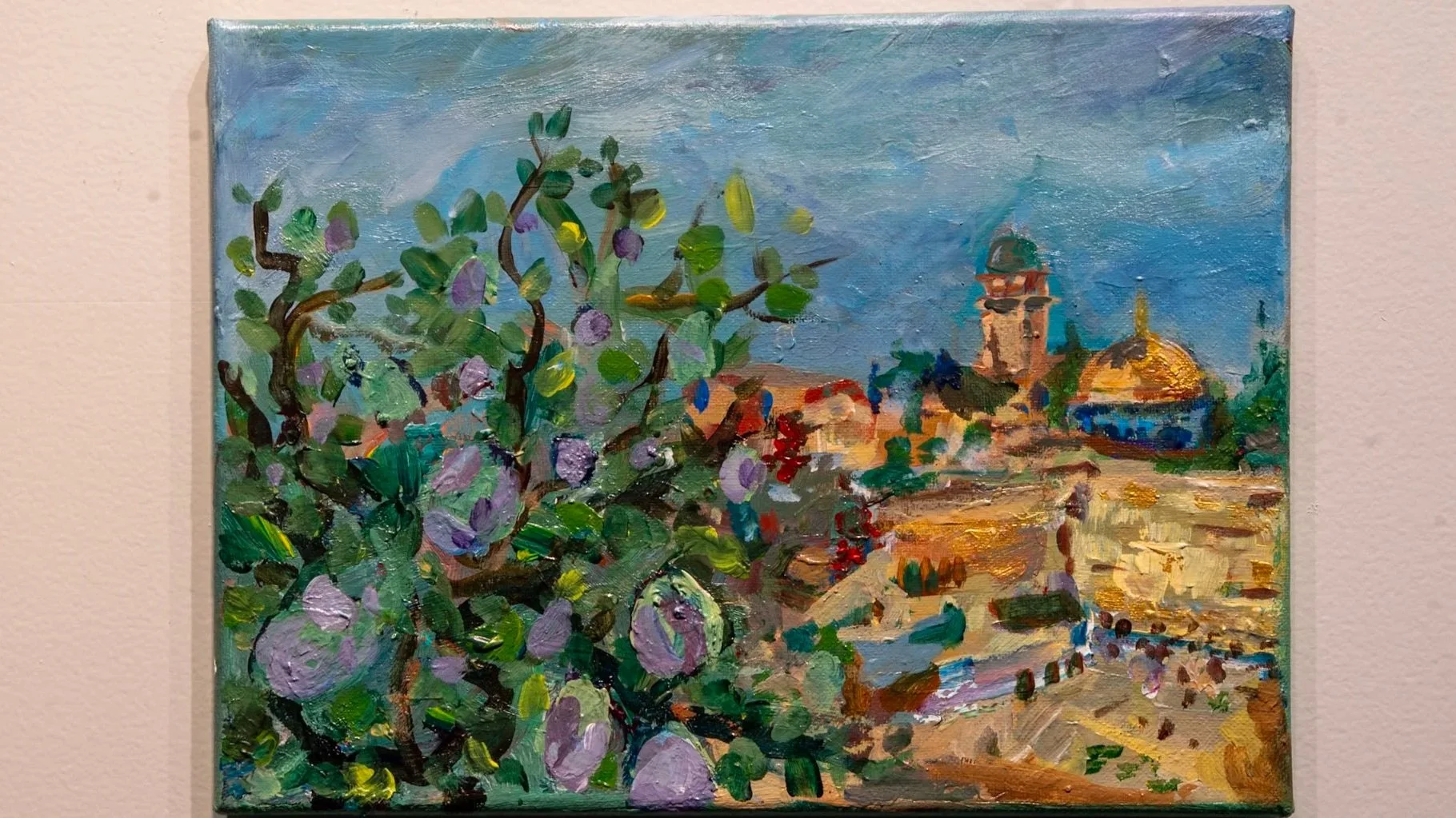

Holy Land, Blessing for Peace, by Micah Steinerman

9x12 in. Acrylic on Canvas.

Here, I depict a landscape sacred to both Jews and Muslims, home to the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock. These two holy sites sit in close proximity within the Old City, each a place of intimate prayer. In the foreground, a fruit tree blooms, inspired by olives, grapes, and figs, with olives symbolizing peace.

Notes:

The Dome of the Rock stands on the Temple Mount. Marks location of significance, where Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven.

The Western Wall (Kotel) is a remnant of the Jewish Temple.

-

Material Function, by Aakef Khan, Curator

Digital film, prayer rug, projected light, tayammum box. Dec 2025.

Islamic ritual assigns operational roles to material - water, dust, textile and body. Rather than serve as symbols, they serve as functional components in a system of preparation. Together, these objects work to prepare the believer for daily prayer. This piece explores the internal states associated with Islamic ritual, including purification of the soul and energy release.